5 April 2011

Frederick W. Swimme lived up to his name a long time ago. He worked and lived around water, although he didn’t necessarily swim in it when alligators were in the neighborhood.

But then Swimme had nothing to worry about because alligators don’t spend their time in saltwater and who would expect them in the Wildwoods anyway?

Until one St. Patrick’s Day, a holiday that is often celebrated with a drink or two, or three or four, or even more. Swimme, a Coast Guard warrant officer, suspected there was illegal rum on a boat moored at Cold Spring Harbor between Wildwood Crest and Cape May. What he saw was enough to stop a man from drinking for a lifetime.

Instead of rum he found 280 alligators, all small, except a five footer named Lizzie running loose on the deck of the fishing boat named Nautilus. Built in 1912 in Pocomoke City, Md., Nautilus was captained by a man named Joshua Shivers who originally came to the Wildwoods from the mainland town of Mayville to start a fishing business.

The Shivers family name was famous in early history of the island. E.M. Shivers became mayor of Anglesea from 1890 to 1893 and Herbert Shivers mayor of North Wildwood from 1923 to 1925.

The boat and its captain had been in Long Key of the Florida Keys that winter and Swimme had heard rumors that it hadn’t been an economically successful winter for the boat and as a result it was bringing some illegal rum to the Wildwoods to cover its losses. Swimme grew even more suspicious when he saw a huge packing case being taken ashore, according to a story printed in the New York Herald-Tribune.

“Hey,” he shouted after he boarded the boat, “what have you got there?”

“Alligators,” bluntly replied Harry Countess of the boat’s crew.

At first Swimme thought Countess was giving him a “wise guy answer.”

“Alligators?” said the Coast Guardsman, “We’ll look at those alligators, I guess.”

The doubtful inspector shook the suspended packing case whose nails had been loosened when the boat sailed through stormy weather at Cape Hatteras. Swimme was looking for signs of rum inside the case, like the clinking of bottles. He shook the case so vigorously that the sides open and instead of rum, out came 280 alligators on the pier and deck of the Nautilus.

While this was happening, some of Shivers’ friends were waiting on the deck to welcome him home. As soon as they saw his cargo gone astray they ran the 100 yard dash or reasonable facsimile to what they thought were safer grounds not usually inhabited by alligators. The safer place would have been the ocean which alligators do not enjoy because of its salty content.

One of Shivers’ friends who held his position was a man with the name of Horse Mackerel Samuel Johnson who enjoyed some literary fame in his own right. Johnson, it is said, was a fishing guide for western author Zane Grey for many years. Whether he encountered alligators has not been made clear in local history, but he acted like a veteran in helping to round up the big ‘gator named Lizzie who apparently was a cinch compared to bucking broncos.

Countess, meanwhile, had been doing his balancing act, balancing himself on a railing of the Nautilus while guiding with a hand the hoist in which the packing case was slung. Suddenly he lost his balance and fell onto the alligator’s snout upon which he sat, if not gloriously but somewhat heroically.

Encouragement came from Horse Mackerel.

“Set right where you are, Harry,” yelled Horse Mackerel who was used to dealing with buffalos and wild horses out west but no alligators, “while I get a rope.”

Countess did not have much of a choice.

Horse Mackerel found himself a rope and, using his western experience, “lassoed” Lizzie’s jaws tight so Countess could dismount from the alligator’s snout.

The Herald-Tribune was to say in its account of Countess’ perch, “There wasn’t much else for Mr. Countess to do…..It was easy to see that it would require considerable agility to get up without sacrificing a considerable---essential part of his trousers to Lizzie to say the least.”

Shivers was to explain later that he transported the small alligators here for sale at pet shops .The captured Lizzie was to go to the Philadelphia Zoological Garden. Some of the smaller reptiles may have escaped to nearby marshlands where they could have survived until the cold of the following winter.

Shvers, who lived to the age of 84 and is buried at Baptist Cemetery in Cape May Court House, did more than transport alligators for a living. He also transported humans in party boats and for fishing.

Reptiles and other animals have been in the news frequently during Wildwood’s history.

Henry H.Ottens, one time publisher of the Wildwood Leader and a prominent philanthropist, was in Albuquerque, N.M., one year and he thought it would be a nice idea to transport 30 donkeys from that area to North Wildwood for part of its beach entertainment. Donkeys, known for their stubbornness, didn’t like the idea or maybe it was the sound of the ocean which Albuquerque did not have. So the donkeys broke away to different points on the beach and it took a bit of doing to corral them, the services of Horse Mackerel not being available.

The biggest animal story, told here at length in an earlier edition, involved the 300-pound lion Tuffy who in October of 1938 escaped from his Boardwalk motorcycle act and killed auctioneer Thomas Saito. The lion was later shot and for awhile its head was displayed on the wall in back of a bar of a local tavern.

The event caused city officials to enact a law banning the use of dangerous animals in Boardwalk acts. That law hasn’t always been enacted because elephant and snake shows have often appeared here since then.

Early on in the settling days, wild cows, horses and hogs roamed the land of the Wildwoods-to-be and some of the few residents there used the animals for target practice.

(Information for this article was researched at the Wildwood Historical Society’s George F. Boyer Museum.)

Keepers at Paignton Zoo said the 35-year-old Nile crocodile was found dead in its Crocodile Swamp attraction on Wednesday.

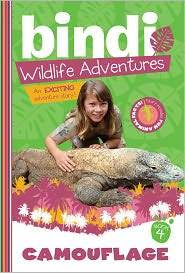

Keepers at Paignton Zoo said the 35-year-old Nile crocodile was found dead in its Crocodile Swamp attraction on Wednesday. At 12 years old, Bindi Sue Irwin, daughter of wildlife conservationists Terri and Steve (the late "Crocodile Hunter") Irwin, is already a celebrity and advocate for animals.

At 12 years old, Bindi Sue Irwin, daughter of wildlife conservationists Terri and Steve (the late "Crocodile Hunter") Irwin, is already a celebrity and advocate for animals.

Back at home, the third adventure has Bindi and her best friend Rosie witnessing the devastating effects of a raging

Back at home, the third adventure has Bindi and her best friend Rosie witnessing the devastating effects of a raging  Suggest these titles to youngsters who are interested in animal tales or eco-adventures. Kids can visit the Australia Zoo

Suggest these titles to youngsters who are interested in animal tales or eco-adventures. Kids can visit the Australia Zoo

Nicholson said the alligator let out a hiss, but he managed to calm the reptile down.

Nicholson said the alligator let out a hiss, but he managed to calm the reptile down. A Thai villager is pictured standing in a devastated area and a worker is seen tending to a crocodile after it escaped from Nakhon Si Thammarat zoo following heavy downpours and landslides.

A Thai villager is pictured standing in a devastated area and a worker is seen tending to a crocodile after it escaped from Nakhon Si Thammarat zoo following heavy downpours and landslides.